Baphomet

From:rahmadqua.blogspot.com

Baphomet (

/ˈbæfɵmɛt/, from

medieval Latin Baphometh,

baffometi,

Occitan Bafometz) is an imagined

pagan deity (i.e., a product of

Christian folklore concerning pagans), revived in the 19th century as a figure of

occultism and

Satanism. Often mistaken for

Satan,

it represents the duality of male and female, as well as Heaven and

Hell or night and day signified by the raising of one arm and the

downward gesture of the other. It can be taken in fact, to represent any

of the major harmonious dichotomies of the cosmos. It first appeared in

11th and 12th century Latin and

Provençal as a corruption of "Mahomet", the

Latinisation of "

Muhammad",

[1] but later it appeared as a term for a pagan idol in trial transcripts of the

Inquisition of the

Knights Templar

in the early 14th century. The name first came into popular

English-speaking consciousness in the 19th century, with debate and

speculation on the reasons for the suppression of the Templars.

[2] Since 1855, the name Baphomet has been associated with a "Sabbatic Goat" image drawn by

Eliphas Lévi.

The name

Baphomet appears in July 1098 in a letter by the crusader Anselm of Ribemont:

Sequenti die aurora apparente, altis vocibus Baphometh

invocaverunt; et nos Deum nostrum in cordibus nostris deprecantes,

impetum facientes in eos, de muris civitatis omnes expulimus.[3]

|

As the next day dawned they called loudly upon Baphometh while we prayed silently in our hearts to God; then we attacked and forced all of them outside the city walls ... [4]

|

A chronicler of the

First Crusade,

Raymond of Aguilers, calls the

mosques Bafumarias.

[5] The name

Bafometz later appears around 1195 in the

Occitan poem "Senhors, per los nostres peccatz" by the

troubadour Gavaudan.

[1] Around 1250 in a poem bewailing the defeat of the

Seventh Crusade by

Austorc d'Aorlhac refers to

Bafomet.

[6] De Bafomet is also the title of one of four surviving chapters of an Occitan translation of

Ramon Llull's earliest known work, the

Libre de la doctrina pueril, "book on the instruction of children".

[7]

Two Templars burned at the stake, from a French 15th century manuscript

When the medieval order of the

Knights Templar was suppressed by King

Philip IV of France, on October 13, 1307, Philip had many

French Templars simultaneously arrested, and then

tortured

into confessions. Over 100 different charges had been leveled against

the Templars. Most of them were dubious, as they were the same charges

that were leveled against the Cathars

[8] and many of King Philip's enemies; he had earlier kidnapped

Pope Boniface VIII and charged him with near identical offenses of heresy, spitting and urinating on the cross, and

sodomy. Yet

Malcolm Barber observes that historians "find it difficult to accept that an affair of such enormity rests upon total fabrication".

[9] The "

Chinon Parchment

suggests that the Templars did indeed spit on the cross," says Sean

Martin, and that these acts were intended to simulate the kind of

humiliation and torture that a Crusader might be subjected to if

captured by the

Saracens, where they were taught how to commit

apostasy "with the mind only and not with the heart".

[10]

The indictment (acte d'accusation) published by the

court of Rome set forth ... "that in all the provinces they had idols,

that is to say, heads, some of which had three faces, others but one;

sometimes, it was a human skull ... That in their assemblies, and

especially in their grand chapters, they worshipped the idol as a god,

as their saviour, saying that this head could save them, that it

bestowed on the order all its wealth, made the trees flower, and the

plants of the earth to sprout forth."

[11]

The name

Baphomet comes up in several of these confessions. Peter Partner states in his 1987 book

The Knights Templar and their Myth,

"In the trial of the Templars one of their main charges was their

supposed worship of a heathen idol-head known as a 'Baphomet'

('Baphomet' = Mahomet = Muhammad)."

[12]

The description of the object changed from confession to confession.

Some Templars denied any knowledge of it. Others, under torture,

described it as being either a severed head, a cat, or a head with three

faces.

[13] The Templars did possess several silver-gilt heads as

reliquaries,

[14] including one marked

capud lviiim,

[15] another said to be

St. Euphemia,

[16] and possibly the actual head of

Hugh de Payns.

[17] The claims of an idol named Baphomet were unique to the Inquisition of the Templars.

[18][19] Karen Ralls, author of the

Knights Templar Encyclopedia, argues that this is significant: "There is no mention of Baphomet either in the

Templar Rule or in other medieval period Templar documents".

[20]

Gauserand de Montpesant, a knight of Provence, said

that their superior showed him an idol made in the form of Baffomet;

another, named Raymond Rubei, described it as a wooden head, on which

the figure of Baphomet was painted, and adds, "that he worshipped it by

kissing its feet, and exclaiming, 'Yalla,' which was," he says, "

verbum Saracenorum,"

a word taken from the Saracens. A templar of Florence declared that, in

the secret chapters of the order, one brother said to the other,

showing the idol, "Adore this head—this head is your god and your

Mahomet."

[21]

Modern scholars such as Peter Partner and Malcolm Barber agree that the name of Baphomet was an

Old French corruption of the name

Muhammad, with the interpretation being that some of the Templars, through their long military occupation of the

Outremer,

had begun incorporating Islamic ideas into their belief system, and

that this was seen and documented by the Inquisitors as heresy.

[22] Alain Demurger, however, rejects the idea that the Templars could have adopted the doctrines of their enemies.

[23]

Helen Nicholson writes that the charges were essentially

"manipulative"—the Templars "were accused of becoming fairy-tale

Muslims."

[23] Medieval Christians falsely believed that Muslims were

idolatrous and worshipped Muhammad as a god, with

mahomet becoming

mammet in English, meaning an

idol or false god.

[24] This idol-worship is attributed to Muslims in several

chansons de geste. For example, one finds the gods

Bafum e Travagan in a Provençal poem on the life of

St. Honorat, completed in 1300.

[25] In the

Chanson de Simon Pouille, written before 1235, a Saracen idol is called

Bafumetz.

[26] Partner's book provides a quote from a poem written in a

Provençal dialect by a

troubadour

who is thought to have been a Templar. The poem is in reference to some

battles in 1265 that were not going well for the Crusaders:

And daily they impose new defeats on us: for God,

who used to watch on our behalf, is now asleep, and Muhammad [Bafometz]

puts forth his power to support the Sultan.

[12]

[edit] Alternative etymologies

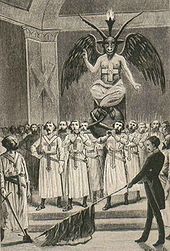

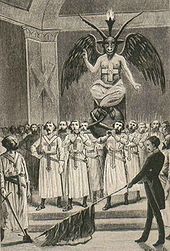

Promotional poster for

Léo Taxil,

Les Mystères de la franc-maçonnerie dévoilés (1886), adapts Lévi's invention.

While modern scholars and the

Oxford English Dictionary[27] state that the origin of the name Baphomet was a probable Old French version of "Mahomet",

[12][22] alternative etymologies have also been proposed:

- In the 18th century, speculative theories arose that sought to tie the Knights Templar with the origins of Freemasonry.[28] Bookseller, Freemason and Illuminist[29] Friedrich Nicolai (1733–1811), in Versuch über die Beschuldigungen welche dem Tempelherrenorden gemacht worden, und über dessen Geheimniß (1782), was the first to claim that the Templars were Gnostics, and that "Baphomet" was formed from the Greek words βαφη μητȢς, baphe metous, to mean Taufe der Weisheit, "Baptism of Wisdom".[30] Nicolai "attached to it the idea of the image of the supreme God, in the state of quietude attributed to him by the Manichean Gnostics", says François Juste Marie Raynouard,

and "supposed that the Templars had a secret doctrine and initiations

of several grades" which "the Saracens had communicated ... to them."[31] He further connected the figura Baffometi with the pentagram of Pythagoras:

What properly was the sign of the Baffomet, 'figura

Baffometi,' which was depicted on the breast of the bust representing

the Creator, cannot be exactly determined.... I believe it to have been

the Pythagorean pentagon (Fünfeck) of health and prosperity: ... It is

well known how holy this figure was considered, and that the Gnostics

had much in common with the Pythagoreans. From the prayers which the

soul shall recite, according to the

diagram of the Ophite-worshippers, when they on their return to God are stopped by the

Archons,

and their purity has to be examined, it appears that these

serpent-worshippers believed they must produce a token that they had

been clean on earth. I believe that this token was also the holy

pentagon, the sign of their initiation (τελειας βαφης μετεος).

[32]

- Emile Littré (1801–1881) in Dictionnaire de la langue francaise asserted that the word was cabalistically formed by writing backward tem. o. h. p. ab an abbreviation of templi omnium hominum pacis abbas,

'abbot' or 'father of the temple of peace of all men.' His source is

the "Abbé Constant", which is to say, Alphonse-Louis Constant, the real

name of Eliphas Lévi.

- Arkon Daraul proposed that "Baphomet" may derive from the Arabic word أبو فهمة Abu fihama(t), meaning "The Father of Understanding".[33] "Arkon Daraul" is widely thought to be a pseudonym of Idries Shah (1924–1996).

- Dr. Hugh J. Schonfield (1901–1988),[34] one of the scholars who worked on the Dead Sea Scrolls, argued in his book The Essene Odyssey that the word "Baphomet" was created with knowledge of the Atbash substitution cipher, which substitutes the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet

for the last, the second for the second last, and so on. "Baphomet"

rendered in Hebrew is בפומת; interpreted using Atbash, it becomes שופיא,

which can be interpreted as the Greek word "Sophia", or wisdom. This theory is an important part of the plot of The Da Vinci Code. Professor Schonfield's theory however cannot be independently corroborated.Joseph Freiherr von Hammer-Purgstall

Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall

(1774-1856) associated a series of carved or engraved figures found on a

number of supposed 13th century Templar artifacts (such as cups, bowls

and coffers) with the Baphometic idol.

In 1818, the name Baphomet appeared in the essay by the Viennese Orientalist

Joseph Freiherr von Hammer-Purgstall,

Mysterium

Baphometis revelatum, seu Fratres Militiæ Templi, qua Gnostici et

quidem Ophiani, Apostasiæ, Idoloduliæ et Impuritatis convicti, per ipsa

eorum Monumenta[35] ("Discovery of the Mystery of Baphomet, by which the Knights Templars, like the Gnostics and

Ophites, are convicted of Apostasy, of Idolatry and of moral Impurity, by their own Monuments"), which presented an elaborate

pseudohistory constructed to discredit

Templarist Masonry and, by extension, Freemasonry itself.

[36] Following Nicolai, he argued, using as archaeological evidence "Baphomets" faked by earlier scholars

[citation needed] and literary evidence such as the Grail romances, that the Templars were

Gnostics and the "Templars' head" was a Gnostic idol called Baphomet.

His chief subject is the images which are called

Baphomet ... found in several museums and collections of antiquities, as

in Weimar ... and in the imperial cabinet in Vienna. These little

images are of stone, partly hermaphrodites, having, generally, two heads

or two faces, with a beard, but, in other respects, female figures,

most of them accompanied by serpents, the sun and moon, and other

strange emblems, and bearing many inscriptions, mostly in Arabic.... The

inscriptions he reduces almost all to

Mete[, which] ... is, according to him, not the Μητις of the Greeks, but the

Sophia, Achamot Prunikos

of the Ophites, which was represented half man, half woman, as the

symbol of wisdom, unnatural voluptuousness and the principle of

sensuality.... He asserts that those small figures are such as the

Templars, according to the statement of a witness, carried with them in

their coffers.

Baphomet signifies Βαφη Μητεος,

baptism of Metis, baptism of fire, or the

Gnostic baptism, an

enlightening of the mind, which, however, was interpreted by the Ophites, in an obscene sense, as

fleshly union....

the fundamental assertion, that those idols and cups came from the

Templars, has been considered as unfounded, especially as the images

known to have existed among the Templars seem rather to be images of

saints.

[37]

Hammer's essay did not pass unchallenged, and F.J.M. Raynouard published an "Etude sur 'Mysterium Baphometi revelatum'".

[38] Charles William King criticized that Hammer had been deceived by "the paraphernalia of ...

Rosicrucian or

alchemical quacks,"

[39] and Partner agreed that the images "may have been forgeries from the occultist workshops."

[40]

At the very least, there was little evidence to tie them to the Knights

Templar—in the 19th century some European museums acquired such

pseudo-Egyptian objects,

[citation needed] which were catalogued as "Baphomets" and credulously thought to have been idols of the Templars.

[41]

Eliphas Lévi

Later in the 19th century, the name of Baphomet became further associated with the

occult. In 1854,

Eliphas Lévi published

Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie

("Dogmas and Rituals of High Magic"), in which he included an image he

had drawn himself which he described as Baphomet and "The Sabbatic

Goat", showing a winged humanoid goat with a pair of breasts and a torch

on its head between its horns (

illustration, top). This image

has become the best-known representation of Baphomet. Lévi considered

the Baphomet to be a depiction of the absolute in symbolic form and

explicated in detail his symbolism in the drawing that served as the

frontispiece:

[42]

The goat on the frontispiece carries the sign of the

pentagram on the forehead, with one point at the top, a symbol of light, his two hands forming the sign of

occultism, the one pointing up to the white moon of

Chesed, the other pointing down to the black one of

Geburah. This sign expresses the perfect harmony of mercy with justice. His one arm is female, the other male like the ones of the

androgyne of

Khunrath,

the attributes of which we had to unite with those of our goat because

he is one and the same symbol. The flame of intelligence shining between

his horns is the magic light of the universal balance, the image of the

soul elevated above matter, as the flame, whilst being tied to matter,

shines above it. The beast's head expresses the horror of the sinner,

whose materially acting, solely responsible part has to bear the

punishment exclusively; because the soul is insensitive according to its

nature and can only suffer when it materializes. The rod standing

instead of genitals symbolizes eternal life, the body covered with

scales the water, the semi-circle above it the atmosphere, the feathers

following above the volatile. Humanity is represented by the two breasts

and the androgyne arms of this sphinx of the occult sciences.

Lévi's depiction is similar to that of the

Devil in early

Tarot cards.

[43] Lévi, working with correspondences different from those later used by

Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers, "equated the Devil Tarot key with

Mercury," giving "his figure Mercury's

caduceus, rising like a phallus from his groin."

[44]

Lévi's depiction, for all its modern fame, does not match the

historical descriptions from the Templar trials, although it may also

have been partly inspired by

grotesque carvings on the Templar churches of

Lanleff in

Brittany and

Saint-Merri in

Paris, which depict squatting bearded men with bat wings, female breasts, horns and the shaggy hindquarters of a beast,

[45][unreliable source] as well as

Viollet-le-Duc's vivid

gargoyles that were added to

Notre Dame de Paris about the same time as Lévi's illustration.

Goat of Mendes

Lévi's now-familiar image of a "Sabbatic Goat" shows parallels with works by the Spanish artist

Francisco Goya, who more than once painted a "

Witch's Sabbath"; in the version ca. 1821-23,

El gran cabrón now at the Prado, a group of seated women offer their dead infant children to a seated goat. In

Margaret Murray's survey of

The Witch-Cult in Western Europe, the devil was said to appear as "a great

Black Goat with a

Candle between his Horns".

[46]

Lévi called his image "The Goat of

Mendes", presumably following

Herodotus' account

[47]

that the god of Mendes—the Greek name for Djedet, Egypt—was depicted

with a goat's face and legs. Herodotus relates how all male goats were

held in great reverence by the Mendesians, and how in his time a woman

publicly copulated with a goat.

[48] E. A. Wallis Budge writes,

At several places in the Delta, e.g. Hermopolis, Lycopolis, and Mendes, the god

Pan and a goat were worshipped;

Strabo, quoting (xvii. 1, 19)

Pindar,

says that in these places goats had intercourse with women, and

Herodotus (ii. 46) instances a case which was said to have taken place

in the open day. The Mendisians, according to this last writer, paid

reverence to all goats, and more to the males than to the females, and

particularly to one he-goat, on the death of which public mourning is

observed throughout the whole Mendesian district; they call both Pan and

the goat Mendes, and both were worshipped as gods of generation and

fecundity.

Diodorus (

i. 88) compares the cult of the goat of Mendes with that of

Priapus,

and groups the god with the Pans and the Satyrs. The goat referred to

by all these writers is the famous Mendean Ram, or Ram of Mendes, the

cult of which was, according to

Manetho, established by Kakau, the king of the IInd dynasty.

[49]

Historically, the deity that was venerated at Egyptian Mendes was a

ram deity

Banebdjed (literally

Ba of the lord of djed, and titled "the Lord of Mendes"), who was the

soul of

Osiris. Lévi combined the images of the

Tarot of Marseilles Devil card and refigured the ram

Banebdjed as a he-goat, further imagined by him as "copulator in Anep and inseminator in the district of Mendes".

Aleister Crowley

Lévi's Baphomet image employed in the later 19th century to suggest Baphomet worship by

Freemasons.

The Baphomet of Lévi was to become an important figure within the cosmology of

Thelema, the mystical system established by

Aleister Crowley in the early twentieth century. Baphomet features in the Creed of the

Gnostic Catholic Church recited by the congregation in

The Gnostic Mass, in the sentence: "And I believe in the Serpent and the Lion, Mystery of Mystery, in His name BAPHOMET."

[50]

In

Magick (Book 4), Crowley asserted that Baphomet was a divine androgyne and "the hieroglyph of arcane perfection":

The Devil does not exist. It is a false name

invented by the Black Brothers to imply a Unity in their ignorant muddle

of dispersions. A devil who had unity would be a God... 'The Devil' is,

historically, the God of any people that one personally dislikes...

This serpent, SATAN, is not the enemy of Man, but He who made Gods of

our race, knowing Good and Evil; He bade 'Know Thyself!' and taught

Initiation. He is 'The Devil' of the Book of Thoth, and His emblem is

BAPHOMET, the Androgyne who is the hieroglyph of arcane perfection... He is therefore Life, and Love. But moreover his letter is

ayin, the Eye, so that he is Light; and his

Zodiacal image is Capricornus, that leaping goat whose attribute is Liberty.

[51]

For Crowley, Baphomet is further a representative of the spiritual nature of the

spermatozoa while also being symbolic of the "magical child" produced as a result of

sex magic. As such, Baphomet represents the Union of Opposites, especially as mystically personified in

Chaos and

Babalon combined and biologically manifested with the sperm and

egg united in the

zygote.

[citation needed]

Crowley proposed that Baphomet was derived from "Father

Mithras". In his

Confessions he describes the circumstances that led to this etymology:

[52]

I had taken the name Baphomet as my motto in the

O.T.O. For six years and more I had tried to discover the proper way to

spell this name. I knew that it must have eight letters, and also that

the numerical and literal correspondences must be such as to express the

meaning of the name in such a ways as to confirm what scholarship had

found out about it, and also to clear up those problems which

archaeologists had so far failed to solve.... One theory of the name is

that it represents the words βαφὴ μήτεος, the baptism of wisdom;

another, that it is a corruption of a title meaning "Father Mithras".

Needless to say, the suffix R supported the latter theory. I

added up the word

as spelt by the Wizard. It totalled 729. This number had never appeared

in my Cabbalistic working and therefore meant nothing to me. It however

justified itself as being the cube of nine. The word κηφας, the mystic

title given by Christ to

Peter

as the cornerstone of the Church, has this same value. So far, the

Wizard had shown great qualities! He had cleared up the etymological

problem and shown why the Templars should have given the name Baphomet

to their so-called idol. Baphomet was Father Mithras, the cubical stone

which was the corner of the Temple.

As a demon

Lévi's Baphomet is the source of the later

Tarot image of the Devil in the Rider-Waite design.

[53] The concept of a downward-pointing

pentagram

on its forehead was enlarged upon by Lévi in his discussion (without

illustration) of the Goat of Mendes arranged within such a pentagram,

which he contrasted with the

microcosmic man arranged within a similar but upright pentagram.

[54] The actual image of a goat in a downward-pointing pentagram first appeared in the 1897 book

La Clef de la Magie Noire by

Stanislas de Guaita, later adopted as the official symbol—called the

Sigil of Baphomet—of the

Church of Satan, and continues to be used among

Satanists.

Baphomet, as Lévi's illustration suggests, has occasionally been portrayed as a synonym of

Satan or a

demon, a member of the

hierarchy of Hell. Baphomet appears in that guise as a character in

James Blish's

The Day After Judgment. Christian evangelist

Jack Chick claims that Baphomet is a demon worshipped by

Freemasons, a claim that apparently originated with the

Taxil hoax.

[55] Léo Taxil's elaborate hoax employed a version of Lévi's Baphomet on the cover of

Les Mystères de la franc-maçonnerie dévoilés,

his lurid paperback "exposé" of Freemasonry, which in 1897 he revealed

as a hoax satirizing ultra-Catholic anti-Masonic propaganda.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b ab Luy venseretz totz los cas/Cuy Bafometz a escarnitz/e·ls renegatz outrasalhitz ("with his [i.e. Jesus'] help you will defeat all the dogs whom Mahomet

has led astray and the impudent renegades"). The relevant lines are

translated in Michael Routledge (1999), "The Later Troubadours", in The Troubadours: An Introduction, Simon Gaunt and Sarah Kay, edd. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), p. 112.

- ^ "In

the 19th century a fresh impetus was given to the discussion by the

publication in 1813 of Raynouard's brilliant defence of the order. The

challenge was taken up, among others, by the famous orientalist

Friedrich von Hammer-Purgstall, who in 1818 published his Mysterium Baphometis revelatum,

an attempt to prove that the Templars followed the doctrines and rites

of the Gnostic Ophites, the argument being fortified with reproductions

of obscene representations of supposed Gnostic ceremonies and of mystic

symbols said to have been found in the Templars' buildings. Wilcke,

while rejecting Hammer's main conclusions as unproved, argued in favour

of the existence of a secret doctrine based, not on Gnosticism, but on

the unitarianism of Islam, of which Baphomet (Mahomet) was the symbol.

On the other hand, Wilhelm Havemann (Geschichte des Ausganges des Tempelherrenordens, Stuttgart and Tubingen,

1846) decided in favour of the innocence of the order. This view was

also taken by a succession of German scholars, in England by C. G.

Addison, and in France by a whole series of conspicuous writers: e.g. Mignet, Guizot, Renan, Lavocat. Others, like Boutaric, while rejecting the charge of heresy, accepted the evidence for the spuitio and the indecent kisses, explaining the former as a formula of forgotten meaning and the latter as a sign of fraternité!" Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911.

- ^ Migne, p. 475.

- ^ Barber and Bate, p. 29.

- ^ Michaud, p. 497.

- ^ The quote is at Austorc d'Aorlhac.

- ^ The other chapters are De la ley nova, De caritat, and De iustitia.

The three folios of the Occitan fragment were reunited on 21 April 1887

and the work was then "discovered". Today it can be found in BnF fr. 6182. Clovis Brunel dated it to the thirteenth century, and it was probably made in the Quercy. The work was originally Latin, but medieval Catalan translation exists, as does a complete Occitan one. The Occitan fragment has been translated by Diego Zorzi (1954). "Un frammento provenzale della Doctrina Pueril di Raimondo Lull". Aevum 28 (4): 345–49.

- ^ Barber 2006, p. 204.

- ^ Barber 2006, p. 306.

- ^ Martin, p. 138.

- ^ Michelet, p. 375.

- ^ a b c Partner, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Read, p. 266.

- ^ Martin, p. 139.

- ^ "Per

quem allatum fuit eis quoddam magnum capud argenteum deauratum pulcrum,

figuram muliebrem habens, intra quod erant ossa unius capitis, involuta

et consuta in quodam panno lineo albo, syndone rubea superposita, et

erat ibi quedam cedula consuta in qua erat scriptum capud lviiim,

et dicta ossa assimilabantur ossibus capitis parvi muliebris, et

dicebatur ab aliquibus quod erat capud unius undecim millium virginum." Procès, vol. ii, p. 218.

- ^ Barber 2006, p. 244.

- ^ "It

is possible that the head mentioned was in fact a reliquary of Hugh of

Payns, containing his actual head." Barber 2006, p. 331.

- ^ National Geographic Channel. Knights Templar, February 22, 2006, video documentary written by Jesse Evans.

- ^ Martin, p. 119.

- ^ Karen Ralls, Knights Templar Encyclopedia: The Essential Guide to the People, Places, Events, and Symbols of the Order of the Temple (New Page Books, 2007).

- ^ Wright, p. 138. Cf. Barber 2006, p. 77; Finke, p. 323.

- ^ a b Barber 1994, p. 321.

- ^ a b Barber 2006, p. 305.

- ^ Games and Coren, pp. 143-144.

- ^ Féraud, p. 2.

- ^ Pouille, p. 153.

- ^ The OED reports "Baphomet" as a medieval form of Mahomet, but does not find a first appearance in English until Henry Hallam, The View of the State of Europe during the Middle Ages, which also appeared in 1818.

- ^ Hodapp, pp. 203–208.

- ^ McKeown, Trevor W. "A Bavarian Illuminati Primer". Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- ^ Nicolai, vol. i, p. 136 ff. Nicolai's theories are discussed by Thomas De Quincey in "Historico-Critical Inquiry into the Origin of the Rosicrucians and the Free-Masons". London Magazine. January, February, March, and June 1824.

See also Partner, p. 129: "The German Masonic bookseller, Friedrich

Nicolai, produced an idea that the Templar Masons, through the medieval

Templars, were the eventual heirs of an heretical doctrine which

originated with the early Gnostics. He supported this belief by a

farrago of learned references to the writings of early Fathers of the

Church on heresy, and by impressive-looking citations from the Syriac.

Nicolai based his theory on false etymology and wild surmise, but it was

destined to be very influential. He was also most probably familiar

with Henry Cornelius Agrippa's claim, made in the early sixteenth century, that the medieval Templars had been wizards."

- ^ Michaud, p. 496.

- ^ "Symbols and Symbolism". Freemasons' Quarterly Magazine (London) 1: 275–92. 1854. p. 284.

- ^ Daraul, Arkon. A History of Secret Societies. ISBN 0-8065-0857-4.

- ^ Hugh J. Schonfield, The Essene Odyssey. Longmead, Shaftesbury, Dorset SP7 8BP, England: Element Books Ltd., 1984; 1998 paperback reissue, p.164.

- ^ Hammer-Purgstall (1818). "Mysterium Baphometis revelatum". Fundgruben des Orients (Vienna) 6: 1–120; 445–99.

- ^ Partner, p. 140.

- ^ "Baphomet", Encyclopedia Americana, 1851.

- ^ In Journal des savants. 1819. pp. 151–61; 221–29. (Noted by Barber 1994, p. 393, note 13.) An abridged English translation appears in Michaud, "Raynouard's note on Hammer's 'Mysterium Baphometi Revelatum'", pp. 494-500.

- ^ King, p. 404.

- ^ Partner, p. 141.

- ^ Hans Tietze illustrated one, in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, in "The Psychology and Aesthetics of Forgery in Art". Metropolitan Museum Studies 5 (1): 1–19. August 1934. p. 1.

- ^ "Le

bouc qui est représenté dans notre frontispice porte sur le front le

signe du pentagramme, la pointe en haut, ce qui suffit pour en faire un

symbole de lumière; il fait des deux mains le signe de l'occultisme, et

montre en haut la lune blanche de Chesed, et en bas la lune noire de

Géburah. Ce signe exprime le parfait accord de la miséricorde avec la

justice. L'un des ses bras est féminin, l'autre masculin, comme dans

l'androgyne de Khunrath dont nous avons dû réunir les attributs à ceux

de notre bouc, puisque c'est un seul et même symbole. Le flambeau de

l'intelligence qui brille entre ses cornes, est la lumière magique de

l'équilibre universel; c'est aussi la figure de l'âme élevée au-dessus

de la matière, bien que tenant à la matière même, comme la flamme tient

au flambeau. La tête hideuse de l'animal exprime l'horreur du péché,

dont l'agent matériel, seul responsable, doit seul à jamais porter la

peine: car l'âme est impassible de sa nature, et n'arrive à souffrir

qu'en se matérialisant. Le caducée, qui tient lieu de l'organe

générateur, représente la vie éternelle; le ventre couvert d'écailles

c'est l'eau; le cercle qui est au-dessus, c'est l'atmosphère; les plumes

qui viennent ensuite sont l'emblème du volatile; puis l'humanité est

représentée par les deux mamelles et les bras androgynes de ce sphinx

des sciences occultes." Lévi, vol. i, pp. 211-212.

- ^ "ס Le ciel de Mercure, science occulte, magie, commerce, éloquence, mystère, force morale. Hiéroglyphe, le diable, le bouc de Mendès ou le Baphomet du temple avec tous ses attributs panthéistiques." Lévi, vol. ii, p. 352.

- ^ Place, p. 85.

- ^ Jackson, Nigel & Michael Howard (2003). The Pillars of Tubal Cain. Milverton, Somerset: Capall Bann Publishing. p. 223.

- ^ Murray, p. 145. For the devil as a goat, see pp. 63, 65, 68-69, 70, 144-146, 159, 160, 180, 182, 183, 233, 247, 248.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories ii. 42, 46 and 166.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories ii. 46. Plutarch specifically associates Osiris with the "goat at Mendes." De Iside et Osiride, lxxiii.

- ^ Budge, vol. ii, p. 353.

- ^ Helena; Tau Apiryon. "The Invisible Basilica: The Creed of the Gnostic Catholic Church: An Examination". Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ^ Crowley, Aleister; Mary. Desti, Leila. Waddell (2004). Magick: Liber ABA, Book Four, Parts I-IV. Hymenaeus. Beta (ed.). York Beach, Me.: S. Weiser. ISBN 0-87728-919-0 9780877289197.

- ^ Crowley, Aleister (1929). The Spirit of Solitude: an autohagiography: subsequently re-Antichristened The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. London: Mandrake Press.

- ^ "Since

1856 the influence of Eliphas Lévi and his doctrine of occultism has

changed the face of this card, and it now appears as a pseudo-Baphometic

figure with the head of a goat and a great torch between the horns; it

is seated instead of erect, and in place of the generative organs there

is the Hermetic caduceus." Waite, part i, § 2.

- ^ "Le

pentagramme élevant en l'air deux de ses pointes représente Satan ou le

bouc du sabbat, et il représente le Sauveur lorsqu'il élève en l'air un

seul de ses rayons.... En le disposant de manière que deux de ses

pointes soient en haut et une seule pointe en bas, on peut y voir les

cornes, les oreilles et la barbe du bouc hiératique de Mendès, et il

devient le signe des évocations infernales." Levi, vol. i, pp. 93-98.

- ^ "Leo Taxil's confession".

References

- Barber, Malcolm (1994). The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42041-5.

- Barber, Malcolm (2006). The Trial of the Templars (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-67236-8.

- Barber, Malcolm; Bate, Keith (2010). Letters from the East: Crusaders, Pilgrims and Settlers in the 12th-13th Centuries. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-6356-0.

- Budge, Ernest Alfred Wallis (1904). The Gods of the Egyptians: or, Studies in Egyptian Mythology. II volumes. London: Methuen & Co.

- Crowley, Aleister (1974). The Equinox of the Gods. New York: Gordon Press.

- Crowley, Aleister (1944). The Book of Thoth; A Short Essay on the Tarot of the Egyptians, being the Equinox, Volume III, No. V. London: Ordo Templi Orientis.

- Crowley, Aleister (1996-12). The Law is for All: The Authorized Popular Commentary of Liber Al Vel Legis sub figura CCXX, The Book of the Law. Louis Wilkinson (ed.). Thelema Media. ISBN 0-9726583-8-6.

- Crowley, Aleister; Mary. Desti, Leila. Waddell (2004). Magick: Liber ABA, Book 4, Parts I-IV. Hymenaeus. Beta (ed.). York Beach, Maine.: Samuel Weiser. ISBN 0-87728-919-0 9780877289197.

- Féraud, Raymond (1858). Sardou, A. L. ed. La vida de Sant Honorat (La vie de Saint Honorat). Paris: P. Janet, Dezobry, E. Magdeleine & Co.

- Finke, Heinrich (1907). Papsttum und untergang des Templerordens: Quellen. Volume II. Muenster: Druck und verlag der Aschendorffschen buchhandlung.

- Games, Alex; Coren, Victoria (2007). Balderdash and Piffle, One Sandwich Short of a Dog's Dinner. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/9761846072352|9761846072352]].

- Hodapp, Christopher (2005). "A crash course in Templar history". Freemasons for Dummies. Indianapolis: Wiley Publishing.

- King, C. W. (1887) [1864]. The Gnostics and their Remains. London: David Nutt.

- Lévi, Eliphas (1861) [1855]. Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie. II volumes (2nd ed.). Paris: Hippolyte Baillière.

- Martin, Sean (2005). The Knights Templar: The History & Myths of the Legendary Military Order. ISBN 1-56025-645-1.

- Michaud, Joseph Francois (1853). The History of the Crusades. Volume III. Trans. W. Robson. New York: Redfield.

- Michelet, Jules, ed. (1851). Le procès des Templiers. II volumes. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.

- Michelet, Jules (1860). History of France. Volume I. Trans. G.H. Smith. New York: D. Appleton.

- Migne, Jacques Paul (1854). Godefridi Bullonii epistolae et diplomata; accedunt appendices.

- Murray, Margaret (1921). The Witch Cult in Western Europe: A Study in Anthropology. Oxford University Press.

- Nicolai, Friedrich (1782). Versuch

über die Beschuldigungen welche dem Tempelherrenorden gemacht worden,

und über dessen Geheimniß; Nebst einem Anhange über das Entstehen der

Freymaurergesellschaft. II volumes. Berlin und Stettin.

- Partner, Peter (1987). The Knights Templar and Their Myth. ISBN 0-89281-273-7. (Previously titled The Murdered Magicians.)

- Paxton, Lee (2010). "Truth and Metaphor". Retreat From Reality. Lulu.com. [1]

Philips, Walter Alison (1911). "Templars". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Philips, Walter Alison (1911). "Templars". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.- Place, Robert M. (2005). The Tarot: History, Symbolism and Divination. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin. ISBN 1-58542-349-1.

- Pouille, Simon de (1968). Baroin, Jeanne. ed. Simon de Pouille: Chanson de Geste. Geneva: Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-02428-0.

- Read, Piers Paul (1999). The Templars. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81071-9.

- Spunda, Franz. Baphomet: Der geheime Gott der Templer: ein alchimistischer Roman. ISBN 3-86552-073-1.

- Waite, Arthur (1911). The Pictorial Key to the Tarot. London: W. Rider.

- Wright, Thomas (1865). "The Worship of the Generative Powers During the Middle Ages of Western Europe". In Knight, Richard Payne. A Discourse on the Worship of Priapus. London: J. C. Hotten.